Headlines:

Turkey-US Relations in the Spotlight Again after Biden’s Armenia Statement

Pakistan May Still Support the Taliban, but Not Like It Used To

Beijing Must Prepare for a Drastic Reversal Ahead of China’s Rise and America’s Fall

Details:

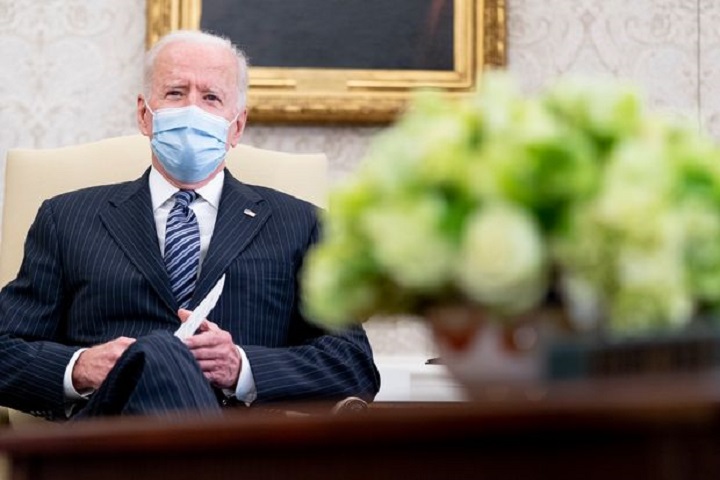

Turkey-US Relations in the Spotlight Again after Biden’s Armenia Statement

Turkey has shown unexpected restraint after US President Joe Biden formally recognized the 1915 massacre of Armenians as genocide by so far avoiding the deployment of rebellious or bellicose rhetoric against its NATO ally. Turkey maintains that the killing of Armenians was not systematically orchestrated and that they died in wartime conditions, leaving the government with two options after Biden’s Saturday statement. Either it can continue to be cautious and dodge a diplomatic crisis with the US at a time when the Turkish lira is depreciating against the dollar, or it can move further into Russia’s orbit and risk seriously damaging relations. Turkey’s reaction is a test for the future of bilateral ties, which are already strained because there is no major support for the country within the US establishment. Biden also delayed his much-awaited telephone conversation with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan until April 23. “Once the Pentagon was Turkey’s biggest supporter inside the US government, now it turned to be Turkey’s biggest adversary in Washington,” Soner Cagaptay, an academic from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told Arab News. “Now Erdogan needs the US more than he thinks Washington needs him. Biden therefore is seizing this opportunity.” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu criticized the US statement. “We have nothing to learn from anybody about our own past,” he tweeted. “Political opportunism is the greatest betrayal to peace and justice. We entirely reject this statement based solely on populism.” The ministry urged Biden to correct this “grave mistake” that had no legal basis, was not supported by any evidence and had “caused a wound that was difficult to repair.” But Turkey did not call for its newly arrived ambassador in Washington, DC, Murat Mercan, for consultation. Nor did it table the possibility of retaliatory action, like restrictions on the use of Incirlik air base by US forces. However the US ambassador to Turkey, David Satterfield, was summoned on Saturday night following the statement so that Ankara could condemn it. Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, Ankara director of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, said that Biden’s statement was seen by most Turks as singling out the country with a double standard approach that would have long-term consequences for perceptions toward the US. “On the other hand one could also argue that anti-Americanism in Turkey is already as bad as it can get,” he told Arab News. [Source: Arab News]

Over the past few years, Erdogan has actively sought to safeguard American interests in Syria, Libya, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the EU, and also in Azerbaijan. Yet, despite this unwavering servitude America has rewarded Erdogan with the Armenian genocide recognition. Does not Erdogan realize that the policy of pleasing a super power is a recipe for political suicide? After all, what has Turkey gained in return—an economy that is on the brink of collapse due to US policies.

Pakistan May Still Support the Taliban, but Not Like It Used To

US President Joe Biden’s April 14 announcement of the withdrawal of combat forces from Afghanistan caught many observers by surprise. The Pakistan Army was not one of them. It has insisted for two decades that foreign military victory over the Taliban was impossible, and that the western presence was as unsustainable as was the Soviets before them. Although US forces have now been in-country for twice as long as the Soviets, the latter’s experience and the Pakistani response are useful guides for what lies ahead. The Soviets in 1979, like the Americans in 2001, had never intended to linger in Afghanistan. But year after year, their friends in Kabul pleaded for just a little more time to turn the corner. The result was that they found themselves stuck, trapped by the inability of their new client regimes to contain the insurgencies that bloomed in the countryside. Unsurprisingly, the Soviet politburo and the White House alike badly wanted out long before the world realised it, held back only by the fear of what a retreat might look like to friends and foes around the globe. But eventually former Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev, just like Mr Biden and his predecessor Donald Trump, simply lost patience and cut his own deal with Pakistan and the Afghan insurgents, with scant regard for the Kabul government’s concerns. Like the Soviets in 1988, the Americans are vowing to remain deeply engaged despite the military pullout, and to continue to prioritise supplying material and diplomatic support to the Kabul government. Certainly it appears that, like the Soviets before them, the US will retain a very substantial intelligence and consular presence in Afghanistan. And even more so than the Soviets, the US is signalling that its forces in the region will strike if its enemies reorganise on Afghan soil. As an additional backstop, the Biden administration is also threatening the Taliban with total diplomatic isolation if they return to power with the same anti-woman and anti-minority behaviour shown in their 1996-2001 stint. Should the Americans be taken seriously? Moscow kept its promises for three long years, despite initial pessimism. When in 1988 the Kremlin signed the Geneva Accords with Pakistan – which set the timetable for Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan – it mistakenly assumed that the Kabul government would collapse like a house of cards after its forces left. In his speech, Mr Biden singled out Pakistan in his announcement as the key to success. Given that the Pakistani government is the closest thing to a friend that the Taliban has, what course of action is it likely to take? One thing we can be sure of is that it won’t look like a replay of the 1990s. In short, Pakistan does not have the same freedom to act in Afghanistan that it did from 1989 to 2001, before the American invasion. Its perennial need to avoid rupture with the US will impose restraints, which in turn greatly improves the Kabul government’s chances of survival. Just as importantly, the Pakistan Army itself has been at the receiving end of extreme violence from cross-border extremism in the past decade, and is now far more cautious about the dangers from a total Taliban victory. Thirdly, Taliban factions are increasingly tying up with other regional powers such as Iran and Russia. Perhaps this explains why the Pakistani government has joined the Afghan and Turkish governments to publicly urge the Taliban to put their guns down and participate in a negotiated political solution to the war. This is a very encouraging sign, but in the end, as ever, the extent of Pakistan’s helpfulness in Afghanistan will be determined by its level of insecurity vis-a-vis India. This is where American, and indeed Chinese, regional policies are essential to bring the temperature between the two countries down. [Source: The National]

Once again America is turning to Pakistan to stabilize Afghanistan, just like it did post-Soviet withdrawal. Back then Pakistan worked with the Taliban to end the civil war and unify Afghanistan under the leadership of the students. Pakistan also viewed this as it strategic depth. It appears, that this time Biden is asking Pakistan to do something similar but via a joint government in Kabul. Otherwise, it will represent a catastrophic failure for America. The truth is that America has been humiliated by another small war, and Pakistan has a golden opportunity to annex Afghanistan via the Taliban for good. Only this action will redeem the military top brass in the eyes of the Pakistani army.

Beijing Must Prepare for a Drastic Reversal Ahead of China’s Rise and America’s Fall

Under the illusionary and self-congratulatory narrative of the inexorable rise of China and the inevitable decline of the United States, many Chinese now think Washington’s “contain and roll back” strategy will prove to be futile and self-defeating, the last hurrah of a superpower that can’t accept its own fall from grace. That is not necessarily so. A hegemon in decline may be even more dangerous than when the global order is stable. In the West, especially the United States, much has been written about the dangers posed by China’s rising global status and its threat to the international order. That narrative is most famously encapsulated in Graham Allison’s 2017 Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? Chinese need to think through the other end of that equation – that is, whether a hegemonic power struggling to retain its dominance will become even more violent, confrontational, ruthless and destructive. Powerful people and empires alike rarely leave the stage in good graces. Many Chinese have talked themselves into believing the inevitable decline of the US. The evidence they point to is not wrong, especially about divisive domestic issues in America: racism and inequalities; the global financial crisis triggered by flawed economic policy, practice and ideology in the US; the failure in Iraq and Afghanistan; the explosion of the Covid-19 pandemic across the US under the incompetent and self-destructive presidency of Donald Trump. All these and more, the Chinese like to point out, are serious self-inflicted wounds. But they are not necessarily fatal. We are already seeing their recovery or the start of one. The upcoming unconditional withdrawal of US combat troops from Afghanistan may look like an embarrassing admission of defeat in America’s longest war. Many Chinese are over-focusing on the political rhetoric and actions of Washington over the South China Sea. It is only one of three major theatres of political and possible military confrontations to contain and roll back America’s adversaries. The other two theatres are eastern Europe and the Black Sea, against Russia, and the Persian Gulf and rest of the Middle East, against Iran. The Chinese need to appreciate what the fight in their own corner of the world means in the context of America’s attempt at restoring global hegemony. China, Russia and Iran are all at the receiving end of the same overall strategic goal. They are being drawn closer together, not because they have much else in common other than a fearsome enemy. But, given the global-economic importance of Asia, America’s anti-China strategies and tactics have to be much more subtle and multidimensional than its overtly militant approach in other parts of the world. That narrative is most famously encapsulated in Graham Allison’s 2017 Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? Chinese need to think through the other end of that equation – that is, whether a hegemonic power struggling to retain its dominance will become even more violent, confrontational, ruthless and destructive. Powerful people and empires alike rarely leave the stage in good graces. What some Chinese may be missing in their analyses is the re-emergence of a remarkably coherent and bipartisan consensus within the US ruling and military classes about the direction of US foreign policy; that is, on what must be done to maintain hegemony after the debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the squandering of the peace dividend after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. In other words, Washington’s domestic agenda may be confused, but its new foreign policy consensus is extraordinarily comprehensive and well-thought out, and is intended to be a guide for a multi-generational struggle. It will not be a new cold war, but a remarkable renewal of purpose recalibrated to maintain global US hegemony for the rest of the 21st century. [Source: South China Morning Post]

China cannot afford to sit on the fence I hope American hegemony will come to an end. China must seize the initiative and challenge America’s primacy in the Asian Pacific by taking back Taiwan and other disputed territories.