1. Why is Europe in another financial crisis?

Europe’s debt crisis is a continuation of the global financial crisis and also the result of how Europe attempted to solve the global financial crisis that brought an end to a decade of prosperity and unrestricted debt. European attempts at defending itself against a deep recession, has now created a new crisis of unsustainable and un-serviceable sovereign debt.

Much of this can be attributed to stimulus packages passed by European governments in order to halt the effects of the economic crisis, especially in preventing massive layoffs. Europe’s heavyweights spent massively on stimulation packages. However such attempts at defending themselves against a deep recession, has now created a sovereign debt crisis. Sovereign debt is the money governments borrow and promise top pay back over a number of years. This gives a government access to large funds instantly, which it repays in instalments over a number of years. As a government guarantee’s the debt, this type of debt is considered the most secure. This is why US treasury bonds are thought to be the most secure investment globally as the US government itself underwrites them.

2. Greece appears to be receiving the bulk of the media coverage, where does it fit into the debt crisis?

Greece joined the Euro zone when it was launched in 1999. By becoming member of the Euro zone Greece’s credit rating was considered the same as Europe’s heavy weights such as France and Germany as they were all now part of the same union. This gave Greece access to finance that it would otherwise not be privileged to and as a result a boom in the Greek economy took place, from 2000 – 2007 Greece was the fasted growing economy in the Euro zone as capital flooded the country. Successive Greek governments went on spending spree’s, creating in turn many public sector jobs, new pension plans and many other social benefits. The spending addiction included high-profile projects such as the 2004 Athens Olympics, which went well over budget.

In keeping with monetary union guidelines, Greece deliberately misreported the country’s official economic statistics. Greece paid Goldman Sachs hundreds of millions of dollars in fees from 2001 for arranging transactions that hid the actual level of borrowing. This enabled Greece to live beyond its means, while hiding its deficit from the EU. Greece’s revision of its deficit figures in May 2010 confirmed its economic statistics had been outright lies. Holders of Greek debt questioned if Greece Would ever be able to pay off the €215 billion in government debt it really owed.

The prospect of a debt default by a European Union nation made headlines and this is why Greece continues to be in the media.

3. Is Greece just an anomaly in the EU?

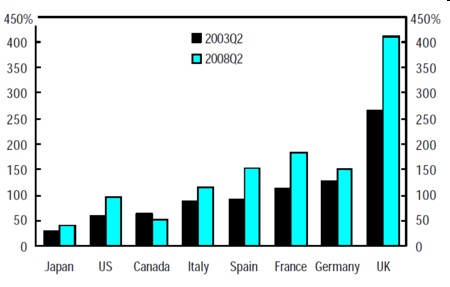

Debt problems are a characteristic of Capitalist economies and in Europe Greece is not the most indebted. PIGS is the acronym the financial markets coined to describe the troubled and heavily-indebted countries of Europe: Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain. Some analysts use PIIGS to include Italy – Europe’s longstanding biggest debtor. Many of the nations that have recently joined the EU have also gone down the path of Greece and taken on lots of debt to fund their economies. Greece is the latest sick man of Europe. It is now officially on the long list of European states that are considered the sick men of Europe. Total gross debt as the graph shows is debt owed by nations that is both short term and long term debt. Europe’s heavyweights all have debt which outstrips their national output.

4. Why has it taken the EU so long to develop a plan on how to tackle the crisis, considering the potential ramifications?

The Greek debt crisis has festered for months with no concrete decision coming forth from EU member states. A bailout package for Greece has been agreed in principal, however this package has many questions marks over it, in terms of it materialising. This is because Germany exacerbated the response. The European Union as a model of unification engenders such a fractured response.

As most of Europe is still recovering from the credit crunch, many have just come out of recession and are witnessing very fragile recoveries. Unemployment is still high and many governments are finding themselves having to slash government’s budgets when tax revenues are falling. A number of European governments have gone to great lengths to impose austerity measures on their domestic populations and hence are in no position to be bailing out a foreign nation. For these reason each of the constituents of the Euro zone looked after their own interests and pushed for Europe’s backbone – Germany, to come to Europe’s rescue. German public opinion was strongly opposed to the use of German funds to bailout Greece, especially after it failed to adhere to the rules of Monetary Union. Germany believes Greece should be taught a lesson on monetary and fiscal discipline.

The Maastricht treaty specifically states that EU funds cannot be used to bailout member states, this is why constituent member states have to use their domestic budgets for any bailout. Germany refused to foot the bill completely and this has only delayed the EU response. In the end a unified Europe only complicated the response.

5. Does this signal the end of the European Union?

Over a period of nearly 60 years the European Union has become an integrated whole through unifying its markets, through a single currency and now through the Lisbon treaty which will streamline decision making and empower Europe to emerge as a continental entity. The European Union has today expanded well beyond its original founder states. Consensus on how far enlargement should go and how deep integration should be continues to plague the union. Member states are reluctant to relinquish their sovereignty to bureaucrats in Brussels or leave key decision making to the two nations that dominate the EU – Germany and France. A union of smaller states into a larger political union is a weak method of amalgamation. It lacks the characteristics found in full unification where a people become one nation. A union as a method of binding peoples and nations is always prone to political differences as it continues to recognise the sovereignty of constituent nations, this leaves it open to fracture and this is the EU’s fundamental problem – it has now institutionalised the national interests of its constituents, this will always delay and complicate the EU’s surge forward.

The debt crisis has severely dented the credibility of the Euro as it was only as strong as its weakest link. It is far fetched to suggest the EU is coming to an end; this is because politically France created the EU in order to strengthen itself and it will not allow the EU to collapse as a political project. Whilst Germany the economic backbone of the EU would protect the EU as it’s Europe’s markets that Germany benefits from.