John Kerry’s – the U.S Secretary of State – claim that the military had restored democracy in Egypt by ousting Mursi has numerous indications. It provided an exposition to an increasingly stark reality; the faltering of the Greater Middle East Initiative. This brief policy analysis will example the implications of the turbulent events in Egypt on U.S foreign policy. It will be argued that the United States failed in propagating the GMEI and planted the seeds of its own demise.

Birth of the Greater Middle East Initiative

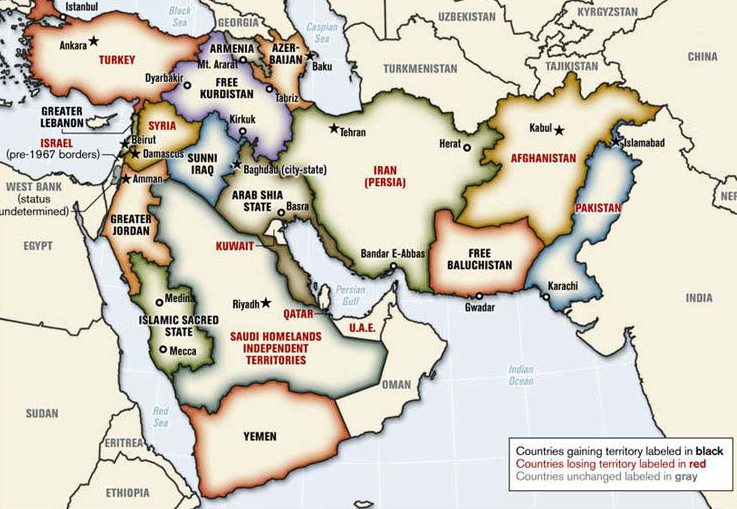

The chief function of the colonial-proxy state in the Middle East is the provision of Security – through maintaining regional stability, protecting trade routes, and so forth. Egypt, as Tamim al-Barghouti explains, has been a chief provider of ‘Security’ vis-à-vis the Authoritarian regime controlled by native-elites who appropriated ‘the State’ to do so. However, the events of 9/11 and the failure of ‘hard power’ in quelling extremism confirmed what many policy-makers had warned; a shift in policy was necessary – more specifically a shift from hard-power to an employment of ‘soft-power’. In 2007 a policy-research team led by Madame Albright urged the U.S to co-opt “Moderate Islamist” and adopt a “politics of inclusion”. The general blueprint of this shift became known as the ‘Greater Middle East Initiative’. The logic behind the initiative was that Authoritarian regimes only perpetuated instability and the native-elites failed to quell extremism and thus a new more democratic and ‘legitimate’ regimes – who draw upon more the specifics of the region as opposed to imposing alien modes of governance. Put briefly, a domesticated democracy which would preserve neo-liberal interests in the Middle East. The “Moderate” Muslim Brotherhood, which had been normalized and accepted the regional and international parameters of the state-system were ideal candidates. An Arab Spring provided the U.S with an opportunity to push forth its nascent initiative.

The Mechanisms of Failure: Old Wine, New Bottle

The optimism of policy-makers and analyst following the rise of the Brotherhood in Egypt to power was soon overshadowed by the underlying complexities of reform in the Muslim world. The chief obstacle being; the Arab Spring and its Islamic orientation represented a call for a ‘new’ phase whereas the existing politico-economic infrastructure was designed precisely to preserve the ‘old’. The old-elites had appropriated ‘the State’ i.e. infrastructure following the 1952 revolution in order to preserve their economic and political hegemony. Furthermore, the premature abortion of the revolution was based on a ‘road-map’ between the ‘old-elites’ represented at the time by the Military and the ‘new-elites’ represented by the Muslim Brotherhood was made convenient in that both party’s accepted the existing politico-economic landscape. After the euphoria of ousting Mubarak had rescinded, the continuity of Mubarakism became a major point of discontent. An example of such continuity being the liberalization of Egypt’s economy, such as Mursi’s desire to obtain an IMF loan, protests flared in Port Said, a scene reminiscent of the Mubarak era. In short, the U.S administrations strategy fell short of the required structural change of the robust authoritarian infrastructure.

Additionally, a reform of the system meant that the ‘old-elite’ would not be entirely uprooted but rather marginalized and replaced. Making an already dysfunctional system all the more ossified and stagnant due to a political deadlock brought about the competing old ‘native-elites’ versus new ‘native-elites. Paradoxically, this meant that both ‘elites’ would fail to provide the U.S with the required provision as their conflict perpetuated instability which were created polarizing societal groups. In reality, the preservation of the ancien regime required that a deal be brokered between the ‘new’ and the ‘old’ – a deal expressed by Mursi’s dismissal of Tantawi and Annan, under American auspices, and bringing to light a long-time U.S-friendly ‘Abd al-Fattah as-Sisi.

Concluding Remarks

In the end, this deal planted the seeds for its own demise and the demise of the U.S backed GMEI because it exacerbated the very same mechanisms (of instability) which the GMEI sought to avoid. Public unrest flared, societal groups were further polarized with both camps realizing that the political compromise was tattering t their expense. The power-struggle eventually led to the ousting of Mursi and the reintroduction of military-backed rule. U.S officials refused to call it a coup d’état and remained largely ambiguous on the administrations official stances. The Obama Administration came to realize ‘new’ had failed in providing the ‘Security’ needed whereas the Iron-fist ‘Old’ elite were fully capable and willing to do so. Accordingly, the John Kerry eventually praised the ousting of Mubarak – paradoxically –as a democratic move. In doing so, he further damaged the prospects of the GMEI which called for the U.S to be a leader in democracy promotion. And overall, the politics of inclusion and ‘Democracy’ has been severely discredited. One is left asking what options the U.S can pursue following its blunders with hard-power in Iraq and Afghanistan, and its more recent blunders with ‘democracy promotion’.